|

|

|

Early Black Churches, Schools and Organizations that Built Binghamton

From the beginning it was a close-knit, caring community that would endure great hardship and discrimination, but would contribute greatly to the overall growth and success of Binghamton and Broome County – and it all started at church.

“Nothing is more powerful than the black church experience.” Barack Obama During the early 19th century as African-Americans arrived in Binghamton, many settled in the vicinity of Susquehanna Street. Initially church services and community gatherings were held in homes, but it wasn’t long before two small chapels were established, owned and occupied by African-Americans. Both were Methodist, and they were referred to as “African Methodist Episcopal.” One was known as AME Zion Church and the other, AME Bethel Church. AME Zion was the first Black church in Broome County. It was organized in 1838 and located about where Columbus Park is now. During the early 1860s abolitionist Jermain Wesley Loguen, known as the “King of the Underground Railroad,” served as pastor of the church. AME Bethel Church was built in 1844 and was located at Susquehanna Street. It is very likely that both churches, AME Zion and AME Bethel, played an active role in the Underground Railroad, providing food and shelter to its travelers. AME Bethel closed around 1930 and the congregation merged with AME Zion Church. Both buildings were eventually demolished and the congregation relocated to Trinity AME Zion Church at Oak Street. In the 1920’s two more Black churches were established – Beautiful Plain Baptist Church at 49 Pine Street, and the Church of God and Saints of Christ Jewish Tabernacle at Sherman Place, just a couple doors down from AME Zion. Early churches provided much more than spiritual guidance for the Black community. They were community centers. Life centered around the church. Binghamton’s first Black churches led directly to the establishment of primary schools, trade schools, and civil rights organizations for the social, political and financial advancement of this area’s Black community.

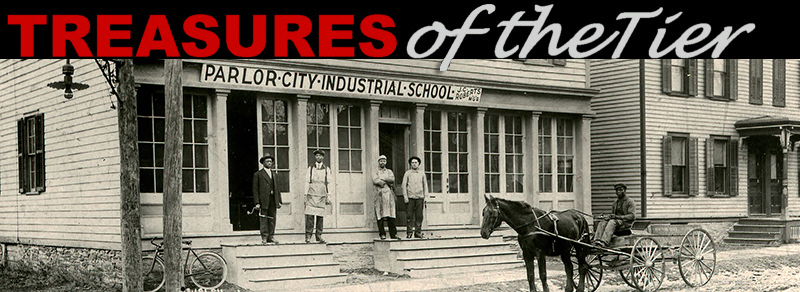

THE FIRST BLACK SCHOOLS Prior to 1861 a “school for colored children” was located near Carroll and Fayette streets. The school did not have a dedicated teacher and was not under supervision of the Board of Education. Then in 1861 a small house on Hawley Street was set up as another school. It continued to serve the African-American community for eleven years, and it is interesting to note that Amelia Loguen, daughter of abolitionist Reverend Jermain W. Loguen, and renowned educator and activist Edmonia Highgate, both served as teachers at this school. Finally in 1872, African-American pupils were assigned to general public schools. By the end of the 19th century basic education was provided but more was needed. Employment opportunities for African-Americans at this time were extremely limited, and Reverend John Roberts, pastor of the AME Zion Church, saw a need for practical trade-school education. In 1910, Roberts, along with two other officers of the church, Thomas Crawley and Leonard Thomas, established the “Parlor City Industrial School.” First meetings were held at the church, then in 1911 the school moved to a building at Fayette Street. The advertised goal of the school was “to teach men and women to become more efficient as laborers and domestics.” Instruction was provided for furniture repair, upholstering and house cleaning. Around that same time, Fred Hazel came to Binghamton. Having graduated from an industrial school in Virginia, Hazel saw a need to provide similar schooling, job training and job placement for the local Black community. In 1912 he founded the “Binghamton Normal Industrial and Agricultural Institute.” Like the Parlor City school, meetings were first held at AME Zion Church. Hazel then obtained 105 acres of land adjacent to Ross Park, where cottages, classrooms and a chapel were built. Female students were trained in sewing and domestic service, and male students in painting, upholstering and carpentry. The Normal Institute continued to operate for three years, but ultimately closed due to lack of funds. The Parlor City Industrial School moved to State Street in the 1920s and later became known as the “Industrial Furniture Company,” which continued to operate into the 1960s.

ADVOCACY, ORGANIZATION AND THE NAACP Fred Hazel and Leonard Thomas were active with Binghamton’s first African-American churches. Both were instrumental in establishing educational centers, and both worked for years to organize and advocate for the social, political and financial advancement of this area’s Black community. In 1907, Thomas formed a local branch of the “United Order of True Reformers,” an organization designed to help African-American members with real estate and insurance programs. Fred Hazel formed a fundraising organization known as the “Frederick Douglass Lyceum of Binghamton,” and a few years later organized the “Binghamton Colored Civic League.” When it was announced that a controversial new motion picture, D.W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation,” was scheduled to play in a local theater, Hazel and the Civic League took a stand against it. As Hazel put it, “the movie is a travesty on history, a breeder of racial antipathy magnifying the faults of the colored race, while glorifying the lawlessness of the whites.” It came as no surprise that the movie played, at both the Armory Theater and Stone Opera House, but not without strong objection by Binghamton’s Black community. Hazel’s Civic League also took issue with the local press and their practice of identifying African-Americans by race in their reporting. Finally, in 1919 a meeting was held at AME Zion Church to establish the first local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Fred Hazel is credited with founding the chapter and Leonard Thomas served as the first president of the organization, followed by Hazel a few years later. Over the years meetings of the local NAACP were held in churches and various other locations, and in 1928 preparations were made to obtain a permanent home for the organization. Drawing from Hazel’s and Thomas’s experience with trade schools, the new facility would include an employment bureau, sewing classes, cooking classes and a nursery for children of working members. But by the early 1930s, membership in the local NAACP had declined below the point of sustainability and it fell dormant. Finally in 1948 a new generation of civil rights advocates led by Clarence McGill saw a need to re-establish a local organization. That year a new Binghamton chapter of the NAACP was formed – to carry on the work of this community’s early Black leaders.

|

|

|