|

|

|

The Great Transcontinental Air Race of 1919

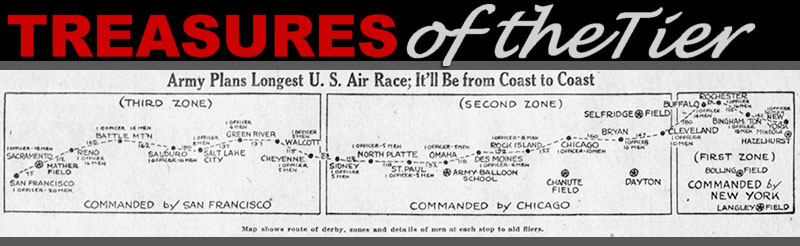

It was summer, 1919. The World War was over and the influenza pandemic had passed. People danced the shimmy to jazz band music at the Arlington, one-piece bathing suits were spotted at Ideal Park – and the airplane had come to town. The idea of sending mail by air was in the news, cross-country flights were occasionally reported and daily commutes by air to the office were seriously envisioned, even to include futuristic spiral landing platforms on the roofs of office buildings. But there was a problem – flying machines were not safe. They frequently crashed, flipped over on landing, ran into things and burst into flames. One popular model, the DH4 Liberty Plane, due to frequent fuel tank fires had earned the nickname “Flaming Coffin.” In an attempt to demonstrate that airplanes could travel safely over long distances, the U.S. Army decided to hold a transcontinental air race. Starting October 8, airplanes would take off from Roosevelt Field on Long Island, fly to the west coast and return. The 5,200-mile round trip would include 20 compulsory stops in each direction. Binghamton was to be the first stop heading west and the last stop on the return before finishing at Long Island. Simultaneously, a few flights were to follow the reverse route, starting on the west coast and flying to the east and back. An open field along the Chenango River at the old Conklin farm – where Otsiningo Park is today – had been used as an airfield, and in anticipation of the transcontinental race, the Binghamton Chamber of Commerce announced that the Conklin Farm airfield would be prepared for “the greatest airplane race ever attempted.” But the Conklin airfield had some rough spots and had not been confirmed as a stop on the race, plus there would be unexpected competition. That summer the Endicott-Johnson Corporation was experiencing major growth. New factories and more workers were needed to double current production. In response, the company purchased 1,000 acres of land west of Union and Endicott, to be known as West Endicott. New factories were planned, as well as housing for 10,000 additional employees – and to accommodate anticipated air commutes to and from Binghamton, an airfield was prepared at a spot known as Laroquette Flats, approximately where Our Lady of Good Council Church is now located, not far from today’s Tri-Cities Airport. As it turned out, the West Endicott field was selected to be the Binghamton control point on the transcontinental route. On October 5 a large DeHaviland biplane with two army pilots landed at the field, checked into Hotel Frederick and the next morning went to work. As reported in The Morning Sun, the two officers “will take formal supervision in behalf of the government of the West Endicott flying field in order to whip it into shape as one of the chief control stations in the great ocean-to-ocean reliability ‘Sky Line Derby’.”

Already, the Chamber of Commerce had marked the field with a huge 100-foot diameter white lime circle with a giant letter “B” in the center, designed to be visible to flyers from several miles away.

Control stations provided refueling and maintenance service for which they stocked an assortment of replacement parts, kept a field log and transmitted messages to adjacent fields on the route. Plans were made to use the wireless tower at Binghamton’s Lackawanna station to receive and transmit departure and arrival times of each machine.

On race day the first planes were expected to reach Binghamton around 11 o’clock and then “to come along with such rapidity as to resemble a flock of sea gulls in flight.”

The race started with 62 entries. The Press reported that three aviators were killed, including one who died in a crash at Deposit, and in another incident, two men survived after “crashing in flames.” Four airplanes were eliminated from the race and the status of several others was unknown – and that was just the first day. On the second day two fliers were rescued by a steamer after their plane “fell into Lake Erie.”

For eleven days Binghamtonians anxiously read daily reports and looked to the sky with great interest. Finally, on October 17 the leader was sighted returning from the west, landing once again at the West Endicott field with just one more short flight to the finish remaining.

The next day Lieutenant Belvin W. Maynard, his mechanic Sgt. William Cline and dog Trixie climbed from their DH4 Liberty Plane at Roosevelt field. An ordained minister, Maynard, known as the flying parson, won the race. A remarkable achievement considering that while over Nebraska the engine crankshaft broke causing a forced landing. Luckily another plane of the same type crashed nearby with an engine that could be salvaged, and by the next morning Maynard and his crew were back in the air.

It was a grueling race, fraught with mechanical failures, bad weather, over 50 crashes and a total of 9 deaths. Of the 62 entries, only eight would complete the race. But it did much to advance the cause of long-distance flight and ultimately resulted in improved safety and reliability of aircraft. It also established a much-needed series of airfields equally distributed across the country.

Following weeks of anticipation and preparation the greatest air race in history was over. At West Endicott the sky was quiet, the crowds were gone and the tents came down. Excitement faded, as did the gigantic white circle-B pattern on the field – and eventually, so did the memory of this historic event.

New York’s Southern Tier has played a significant role throughout the history of manned flight. This year as we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the historic lunar landing, and with it, local contributions to that effort, it is worth remembering that in this area it all started another 50 years before that.

On completion of his 5,200-mile flight, Belvin Maynard climbed from the cockpit with “one small step,” but the great 1919 transcontinental air race represents a giant leap in the development of safe, practical air travel – and this community, along with those at each airfield along the route, played a major role in its success.

|

|

|