|

|

|

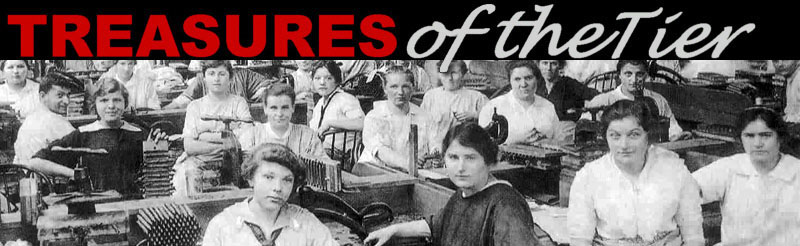

The Hull-Grummond Cigar Company - a Builder of Binghamton

As stated in their advertisement, “There are few places in the land that offer better working and residential conditions than Binghamton! Come to our factory. Learn cigar making. BE ONE OF US!” Not stated in the advertisement was the pay rate… 40 cents for rolling 100 cigars. At a time when the average annual salary was $750, cigar rolling came in far below average. George Hull and his brother moved from Connecticut to Port Crane in the mid 1800’s. At that time cigar making in Binghamton had just begun and George Hull soon set up shop to make cigars. The industry quickly grew and within a few years there were several cigar companies in town. But it was George Hull’s nephew, John Hull Jr., who started a company in 1876 that would help take the industry, and Binghamton, to new heights. Located in what later became known as the Fair Store, the new company thrived. Eventually salesman Fred W. Grummond joined the firm and in 1886 a new four-story Hull-Grummond factory was built near the corner of Water and Henry Streets. A close look at the building today shows two buildings side by side. The building on the left is the original 1886 factory. By 1890 there were over 50 cigar factories in Binghamton and Hull-Grummond was one of the top producers with 300 employees. Demand continued to increase and in 1906, now employing 600 and producing 100,000 cigars daily, Hull had another building constructed adjoining the original structure. With the new building, designed by architect T.I. Lacey “especially for the purpose of a cigar factory”, Hull doubled both his work force and cigar production. At its peak, Binghamton was producing 100 million cigars annually, ranking second in the country only to New York City. The obvious question is “Why Binghamton, and why cigars?”. The answer according to Broome County Historian Gerald Smith, is “railroads and cheap labor.” In the mid 1800’s a canal system was in place, but it was the railroad that would soon establish Binghamton as a transportation hub. At the same time, a continuous influx of immigrants provided a never-ending supply of labor. Toward the end of that century, big things were happening in Binghamton. Transportation, urbanization and immigration all came together in this city, the stage was set for phenomenal growth in manufacturing, and the cigar was the initial product of choice. No matter that tobacco was not locally grown – as advertised, tobacco in Hull-Grummond’s most popular cigar, the Flor de Franklin, “is of the finest types grown in the south, in Wisconsin and Connecticut, and the wrapper is imported from the finest tobacco fields of Sumatra”. By all accounts, key to Hull-Grummond’s success was its founder, John Hull, Jr., driven by a basic desire to produce a quality product. “Binghamton prior to 1890 was principally a producer of scrap-filled cigars”, claimed their advertisements. “The Franklin, a long filler cigar, was created by Mr. Hull and instantly became a success.” It put Binghamton “in a class of cigar providing centers of note.” The good times were not to last. Immediately following World War I, cigarettes were in, cigars were out, and the industry that built this city would die a slow death. By 1920 large areas of the factory were idle and space was leased to another manufacturer… now instead of hand-rolling Franklin cigars, workers stitched Enna Jettick shoes for the Dunn and McCarthy company. Finally, in 1928 the business closed. As reported by the Binghamton Press at the time, “The company at one time was one of the largest employers of labor in the city. The business suffered decline following the World War and the factory has been practically closed since the death of John Hull, Jr. more than a year ago.” At his funeral John Hull Jr. was referred to as “a builder of Binghamton”. A long-time colleague in the industry commented about Hull: “He was one of the first and one of the last great figures in Binghamton’s cigar history. Nobody loved their business more than John Hull loved his, and he paid it all the attention and care of a father.” The building would later serve as an auto parts store, an electrical supply company, and house a variety of other businesses. Today modern offices fill the second and third floors, the vacant fourth floor with exposed brick walls, rafters and wood floors remains virtually unaltered, and since 1997, the first floor has been home to one of Binghamton’s most popular restaurants, the Lost Dog Café. When at the restaurant, take a minute to imagine how it was 100 years ago. Then read the Vaclav Havel quote on the menu: “Hope is not the conviction that something will turn out well but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out”. These words seem to describe the philosophy not just of the current tenant, but also the builder of this historic landmark… “a builder of Binghamton.” As for Binghamton’s other giant, in 1868 John Hull Jr.’s uncle George Hull took a break from his small cigar business and had a 10-foot long, 2-ton figure of a reclining man secretly chiseled out of gypsum and buried on a farm in Cardiff, New York. One year later the stone sculpture would be “discovered” and promoted as a petrified ancient giant, creating one of the greatest hoaxes in American history. But that is another story.

The Cardiff Giant, as displayed at the Farmers' Museum, Cooperstown, New York

|